The Dallas Police Department’s Preliminary Report On The Chaotic First 4 Days Of Police Brutality Protests Has Existed, Unreleased, Since At Least June 12.

Update on August 19, 2020: More than a month after the below report, DPD finally issued its formal report on the first four days of violent police brutality protests in Dallas in late May and early June. You can read our coverage of that report here.

Our initial report follows.

* * * * *

The Dallas Police Department’s preliminary report on its response to a chaotic first four days of still-ongoing police brutality protests in Dallas — including the department’s highly publicized arrest of 674 protesters on the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge on Monday, June 1 — has existed since at least June 12.

On June 5, a week prior to the June 12 filing date listed atop the 13-page document, Mayor Eric Johnson publicly lambasted Dallas Police Chief Renee Hall during an eight-hour city council session for not having concrete information to share in regards to her department’s response to protest activity.

All 14 members of Dallas City Council, and presumably the mayor as well, were emailed the preliminary report by City Manager T.C. Broadnax at 7:24 p.m. on June 17 after he himself received it from city attorneys — either on or before that same date. At city attorneys’ request, Broadnax passed along the document and advised council members not to share the report publicly because of ongoing litigation involving police and the protesters. (Opposing lawyers involved in the case say they are not aware of any legal precedent preventing the document from being publicly released.)

Even as many at Dallas City Hall have been openly calling for increased police transparency in response to public outcry over DPD’s handling of the protests, none have publicly released — or even publicly acknowledged the existence of — the report or its findings over the course of the more-than-month-long period that has passed since they received it. (A majority of that time has fallen during the council’s annual summer recess that runs throughout the entirety of July).

Some city council members we spoke to admitted that they didn’t know the report was in their inboxes until we alerted them to it; they said that they’d “missed it” and only read it for the first time upon our bringing it to their attention. Others said they received the report — but, as one put it, they “didn’t think it was a big deal.” At least two conceded upon being reached for comment that they may have erred in not previously publicizing or releasing the document themselves. Others did not respond to our multiple interview requests.

Central Track has obtained a copy of this “Preliminary After Action Report” on what DPD refers to as the “Protests for Equality” that have been taking place throughout Dallas for the past 54 days. The report exclusively focuses on the events that occurred from May 29 through June 1. Among other things, it confirms certain department use of weapons that Chief Hall has yet to publicly acknowledge.

The report was leaked by an anonymous City Hall employee who had access to it.

Multiple city council members have confirmed that the document we have obtained is the same as the one they received. You can view the report in its entirety here, and also at the bottom of this post.

Here are the juicy highlights of the first four days of protests, according to DPD’s own reporting:

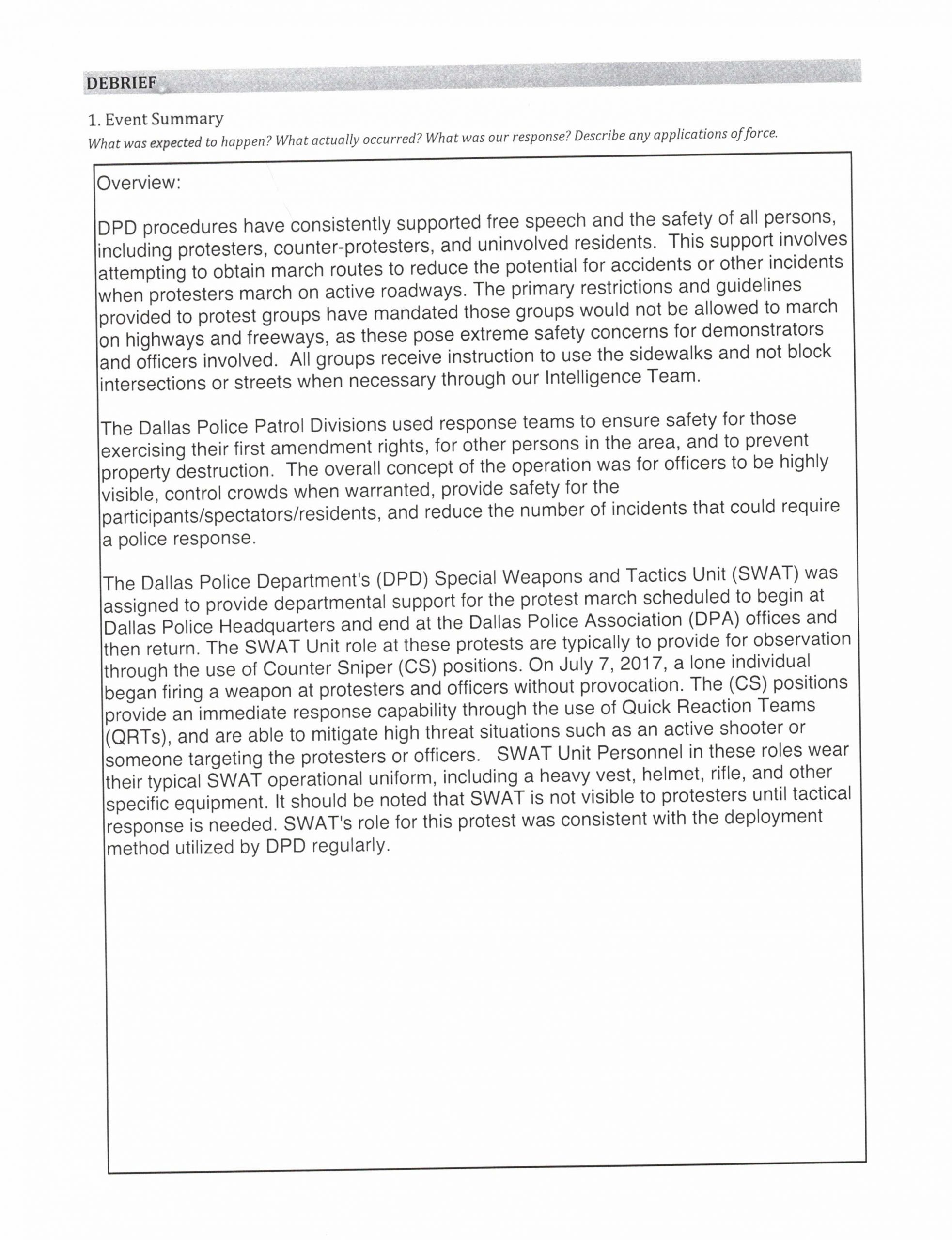

- A total of 81 Dallas Police Department officers of various ranks are reported to have worked the first four days of protests. Together, they logged 5,670.75 hours during that stretch; 2,564 of those hours were logged as “overtime hours.”

- The opening line of the report’s “Event Summary” portion, which details the day-by-day activity of the police response to the first four days of protests, reads as follows: “DPD procedures have consistently supported free speech and the safety of all persons, including protesters, counter-protesters, and uninvolved residents.” On DPD’s goals for its response to the protests, the report reads: “The overall concept of [this] operation was for officers to be highly visible, control crowds when warranted, provide safety for the participants/spectators/residents, and reduce the number of incidents that could requite a police response.”

- Initially, DPD’s SWAT unit was tasked with the observation of the protests through “counter sniper positions.” The report acknowledges the July 7, 2016, Downtown Dallas shooting and killing of five area officers after a recent police brutality protest as its reasoning behind the use of this “counter sniper” tactic. The report, however, misidentifies the date of that shooting as having taken place on July 7, 2017. The report further acknowledges that all uniformed SWAT officers in these “counter sniper” roles were not visible to protesters. SWAT’s role in its response support is said to be “consistent with the deployment method utilized by DPD regularly.”

- Protesters voluntarily made DPD aware of their march route and march start times for Friday, May 29, the first night of conflicts. Along that route, protesters “encountered” and “began to surround” DPD officers at the intersection of Griffin and Young streets, at which point officers at the intersection called in for backup. The report accuses protesters of throwing, among other projectiles, “frozen water bottles” at officers. (We have not previously seen this detail in any other media reports of that night, or of the protests at large, including our own.) The report also says crowds lit “squad cars on fire.” (Independent video reports from that night confirm at least once such incident.) It says DPD received “several shots fired calls” relating to the protests that night. It also acknowledges that officers’ “use of [their] PA only seemed to infuriate the crowd.” Ostensibly in response to these listed actions, SWAT commander Lieutenant Mark Vernon “gave the command to deploy gas” in order to disperse the crowds. Shortly thereafter, SWAT officers began firing “less-lethal” projectiles into the crowds. The back-and-forth continued “throughout the night and into the early morning hours of Saturday” with DPD officers moving from conflict to conflict in armored personnel carriers (APCs). The report justifies this response as follows: “These crowds injured officers, damaged property, burglarized businesses, and committed thefts in the downtown area. Businesses that were impacted include multiple 7/11’s, Neiman Marcus, and other downtown business locations in Deep Ellum.” It reports that 11 SWAT officers were struck by projectiles along with two DPD patrol officers that were also injured. It says one unidentified female officer required stitches for her injuries.

- DPD’s recap of Saturday, May 30, opens by acknowledging that state troopers and members of the Irving Police Department, Garland Police Department and local FBI department’s SWAT teams all joined DPD’s protest response ranks for the day. The report notes that protests “began peacefully” and marched several times throughout Downtown Dallas between regularly returning to their Dallas City Hall starting point, where protesters “reinvigorated themselves by drinking water and sitting in the shade.” When the marches returned to City Hall Plaza a third time, DPD reports “things began to get out of control.” Response teams stationed inside of City Hall and observing the crowds from above then spotted “a white male outfitted with a gas mask and long gun” in the crowd. Though “the crowd did not harm the protester and he freely left the location,” DPD “feared for the man’s safety” and “responded to assist the man.” The crowds that surrounded that DPD response effort reportedly injured at least one officer, at which point SWAT was called in for backup. Because the crowd had “descended into disorderly and uncontrollable behavior,” SWAT officers moved in on the scene “using APCs and a variety of crowd control devices.” The report notes that some protesters “were wearing protective gear and were throwing the gas canisters back at officers.” After clearing City Hall Plaza, officers engaged in multiple similar skirmishes throughout the surrounding areas, deploying various “less-lethal” projectiles and making “multiple arrests” while being “outnumbered.” Throughout the day, DPD “employed similar tactics that had proven effective on Friday night; however, the groups used similar tactics as well by running away from officers and then regrouping to engage in violent activities in another area.” It wasn’t until Sunday morning “when order was finally restored.”

- The report’s Sunday, May 31, recap mostly details its response to the 7 p.m. curfew order that the department had placed on Downtown Dallas and various adjacent neighborhoods earlier in the day. Despite anticipating some 1,000 to 1,500 protesters at various events across the city that day, Sunday “was pretty uneventful,” as some officers “were left to patrol… the targeted areas [inside the curfew zone] that the violence and destruction had taken place [in] the two days prior.” Once 7 p.m. rolled around, the report says individuals within the curfew zone “were given forty minutes for gainful compliance.” Multiple curfew violation arrests were made. Later, SWAT and state troopers are reported to have spent “approximately one hour” using “pepperball, mace and flash bangs” while dispersing another crowd. Officers “did not respond to any other incident for the rest of the night.”

- On Monday, June 1, DPD was prepared “to provide safety for the protesters and to bring to order any criminal violations of the law” at two planned protests throughout the day — but particularly at one organized by the Next Generation Action Network (NGAN), whose event was scheduled to take place after the curfew, but just outside of the curfew zone, at the Frank Crowley Courts Building. According to the report, DPD staff made multiple attempts to contact NGAN leader Dominique Alexander (the organizer behind Friday’s march) to learn about the group’s plans for the night. Over text, the report states, Alexander told Chief Hall that “the group would only be marching in a circle.” According to the report, marchers eventually began their path that night along Riverfront Boulevard before they “made a u-turn on to Trinity Groves.” (There is no road named Trinity Groves; Trinity Groves is a commercial development located more than a mile away from the courthouse, across the Trinity River and over the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge.) After apparently marching north along a road that does not exist, the report states that protesters “neared” the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge, at which point they were met with Dallas County Sheriffs officers who were “staged at the base of the bridge with their lights on.” The report makes no mention of Chief Hall’s repeated claims that protesters were given multiple verbal warnings not to walk onto the bridge; it does say “the crowd disobeyed the officers and began marching on the bridge.” Officers then moved to secure either side of the bridge onto which the protesters were marching. On the bridge, “a large crowd… that had already ignored officer commands (to leave the bridge)” began, according to the report, throwing “water bottles filled with baking soda” at the officers. In response, officers “used pepper ball launchers” to “stop the crowd from moving forward.” Per the report, SWAT further responded by firing two tear gas (CS) canisters onto the bridge. (Chief Hall has not previously confirmed publicly DPD’s use of tear gas on the bridge.) The report notes that wind conditions negatively affected the tear gas’ effect, which the report says DPD used as an attempt to form “a smoke/CS barrier” between officers and protesters. The report denies that the gas was “directed into the crowd” and even says it “was not an attempt to disperse the crowd,” but rather that it was only used to “stop their movement and aggression.” Once the crowd “began to comply,” officers placed “over 600 persons” in custody. The report notes the contraband DPD says it cataloged being carried by protesters: “Several rocks/small pieces of bricks, two handguns, one small hammer, one can of propane, one bottle of lighter fluid, numerous cans of spray paint, and multiple bags of baking soda which can be added to water bottles to make them explode.” (Baking soda and water combine for a common anti-tear gas solution; most middle-schoolers know baking soda and vinegar cause an explosive reaction.) Per the report, the volume of protesters made it too difficult for police to determine who owned which items, so none of the items were confiscated.

- On a sheet asked to determine the successes of the response, the report notes: “Identified the need to separate the downtown corridor into zones to provide greater command and control for commanders monitoring events in these areas.” It provides no answer to the prompt of “How to ensure success in the future.”

- On a sheet asking for improvement suggestions for future operations, the report lists “identify incident commanders processing center established for mass arrest,” “provisions for officers” and “communication with law enforcement.” Under recommendations, it lists: “create a fluid commanders list,” “have identified team for large protest,” “food service team” and “designated channel for communications.”

- An included email sent from the aforementioned SWAT commander Lieutenant Mark Vernon to DPD Deputy Chief Avery L. Moore confirms that Vernon, who had OK’d Friday’s tear gar use, also personally approved of using tear gas and other “less-lethal” force during the clash between protesters and officers on the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge. The email’s verbiage — particularly about the ineffectiveness of the rounds deployed on the bridge — is quoted almost verbatim in the report’s Monday, June 1, recap.

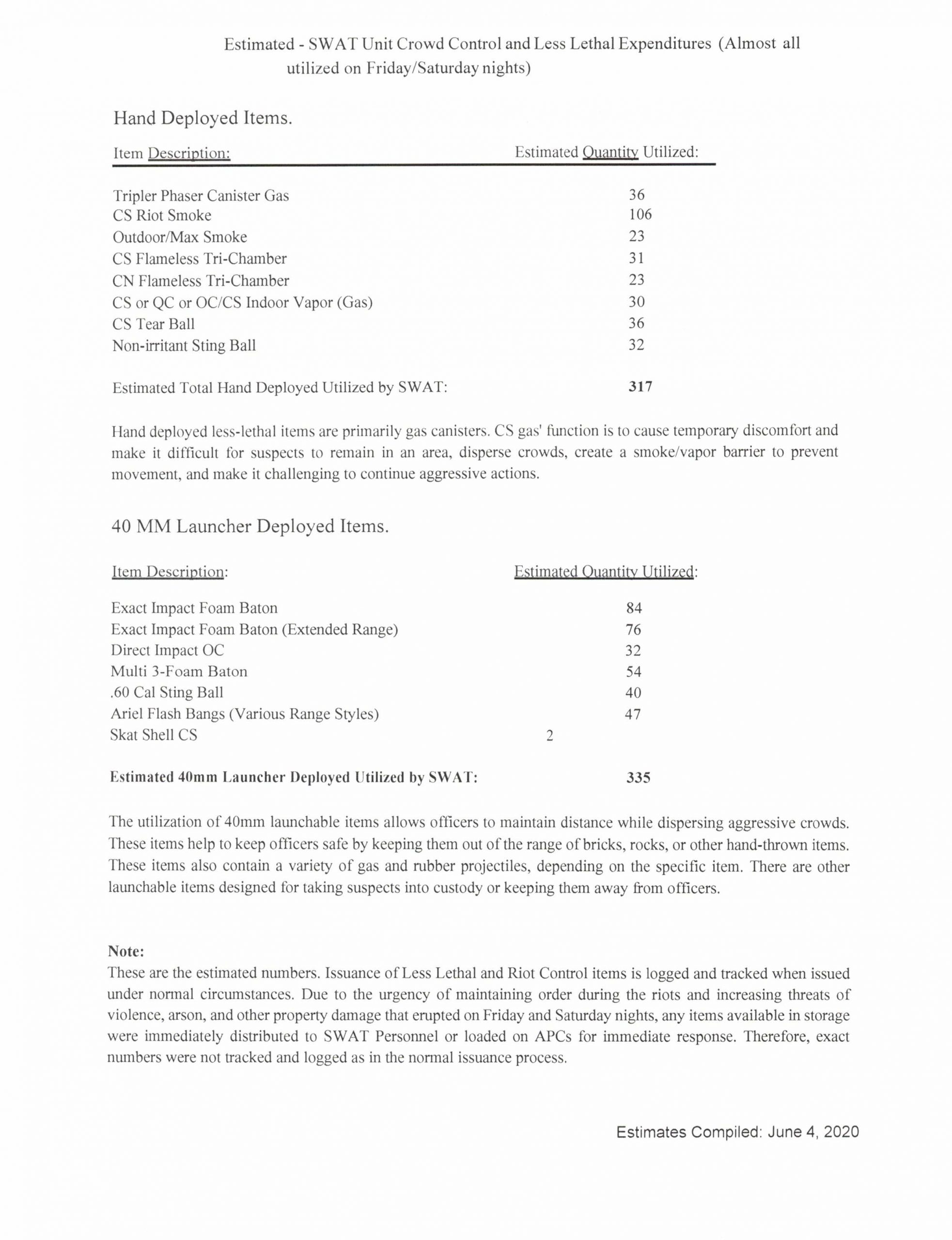

- The final page of the report offers an itemized, if only “estimated,” breakdown of “less lethal expenditures.” In total, it reports 652 projectiles deployed over the first four days of protests, 317 of them “Hand Deployed” and the remaining 335 being “40 MM Launcher Deployed.” The breakdown of ammunition is consistent with our own independent investigations into DPD’s use of its armoury during this same stretch. The report ends by acknowledging that “due to the urgency of maintaining order during the riots and increasing threats” the “exact numbers [of these weapons used] were not tracked and logged.”

In the 39 days since the report’s own stated filing date of June 12, there have been continued calls for Chief Hall’s resignation and DPD officers themselves calling for department reform. All the while, protests calling for policing changes have endured.

Charges against those detained on the bridge have been dropped. So too have the charges against people arrested for breaking DPD’s shortly lived Downtown Dallas curfew.

In response to protester demands, Chief Hall has also announced a new policy — one issued in the name of transparency — for DPD to release body cam footage of incidents relating to officer-involved shootings within 72 hours of those instance’s occurrence.

In the 34 days since Broadnax emailed this after action report to council members on June 17, the city manager, all 14 elected members of Dallas City Council, various city attorneys and several higher-ups at DPD have come into possession of the report. Very few others seem to have seen it until now; a spokesperson for the mayor’s office would not confirm whether Mayor Johnson had read it.

We have not yet been able to confirm whether any members of the Community Police Oversight Board have yet seen the report.

A joint statement credited to both Chief Hall and City Manager Broadnax — issued to Central Track this morning via a City Hall spokesperson responding to our requests for comment from both officials — asserts the following:

- “The June 17 point in time internal draft update was requested by several City Council members.”

- “It was [at that] point in time [a] draft not a final, complete or comprehensive report.”

- “The City Manager’s Office doesn’t release drafts. The City Manager and DPD wanted to provide opportunity for it to be comprehensive and allow time to fully review and investigate additional information provided by the public.”

- “The City Manager’s Office and DPD will continue to be transparent and thorough to avoid misinformation. The June 17 point in time draft provided at several City Council members’ request was not a final, complete or comprehensive report. DPD has spent more than 500 hours reviewing new evidence received since June 17. Members of the public with any additional photos, videos, or information are asked to please use the iWatch Dallas app or email [email protected] by July 31. DPD continues its review and investigation and expects to finalize its report and share it with City Council and the public after the council returns from July recess.”

At least one city council member said they hadn’t previously noticed the report because their inbox has been overrun with “10,000 to 15,000” form petition emails regarding defunding the police. Two more blamed vacation time — in Colorado, specifically — for distracting them from the issue.

“I’m not particularly excited about the use of all this ‘less-lethal’ stuff,” District 11 council member Lee Kleinman said when reached for comment on the report Tuesday night. “But I don’t think there’s anything in this report that hasn’t been said in City Hall briefings or in the press. From a transparency standpoint, [not releasing it yet] is problematic. I think there will be activist reaction, trying to make something of it. But in my district? Nah.”

District 14 council member David Blewett said it “has been a while” since he thought about the report when reached for comment on it Tuesday night. He also acknowledged that the report’s delayed released is “obviously not” a sign of increased DPD or City Hall transparency.

“I didn’t think about it,” he concedes when pressed on the report and its delayed released.

District 12 council member Cara Mendelsohn cautioned that its release may have been held back because, to her understanding, it is still just a “draft.”

Council member Kleinman suggested that the report’s release was being delayed because the overall, larger “event” surrounding DPD’s investigation into its protest response — meaning the demonstrations still taking place across the city — are still ongoing.

The three council members we spoke to on the record now all say they intend to bring the report up as soon as their summer recess ends.

At least one open records request regarding the report’s release was placed on July 1. That request has not yet been fulfilled by the police department.

One former high-ranking DPD officer we spoke with on the condition of anonymity provided the following summation of the report: “Most of it sounds reasonable on its face but that’s because it is very general. They throw bricks; we have SWAT come and fire CS gas. That tells me that leadership didn’t know what they were doing [and] didn’t plan ahead at all. They brought in other agencies because of how bad Friday was and yes, they were needed, but we had never trained with them.”

That same source then added that he’d passed the report along to a former coworker still in DPD’s ranks.

“He’s never seen it,” that former DPD officer said of his old colleague. “He didn’t know this thing was out.”

The Report:

This story has been updated to include statements from Chief Hall and City Manager Broadnax. Avi Adelman contributed to this coverage. Cover photo by Shane McCormick.

Like so many small businesses, we at Central Track face an uncertain future due to the effects of COVID-19. In eight years of operations, we’ve never locked our content from you through subscriptions or paywalls — but, in order to make it out through the other side of all this, we need your help. If you can, please consider supporting our coverage of all things Dallas culture by subscribing to us on Patreon in exchange for exclusive perks or by donating directly through PayPal or Zelle to [email protected].