A Year Later, The Untold Story Of What Happened After A Bizarre Statue Suddenly Appeared In Downtown Dallas And Suggested The City Was Founded By A Cephalopod.

A million lifetimes and 12 months ago, I broke a story about a curious guerrilla art installation suddenly appearing in Downtown Dallas.

The odd set of circumstances that followed then almost broke me.

All this time later, I remain unsettled by the whole thing.

I was complicit in my undoing, I know. You should’ve seen me on October 28, 2019; I really was in rare form. I mean, of course I was. That morning, a loyal reader had passed along a story tip that ticked all my boxes: it was wholly unique; it was decidedly mysterious; it was clever; it was tongue-in-cheek; it was a middle finger to institutionalized norms; it was a little off; it was, for all of its warts, also decidedly informed.

It was more than enough to comprise a good story. Hell, it was damn near everything to which I personally aspire.

Photo by John Bradley.

The story went like this: On his way into work one late October day, a Dallas attorney named John Bradley noticed something along his usual path. Tucked away in an otherwise nondescript corner beneath the hulking Kay Bailey Hutchinson Convention Center stood a silver figure that he was certain he’d never seen before. He would’ve noticed it, no doubt; a statue boasting the body of a man and the head of an octopus wasn’t really the kind of thing you could miss.

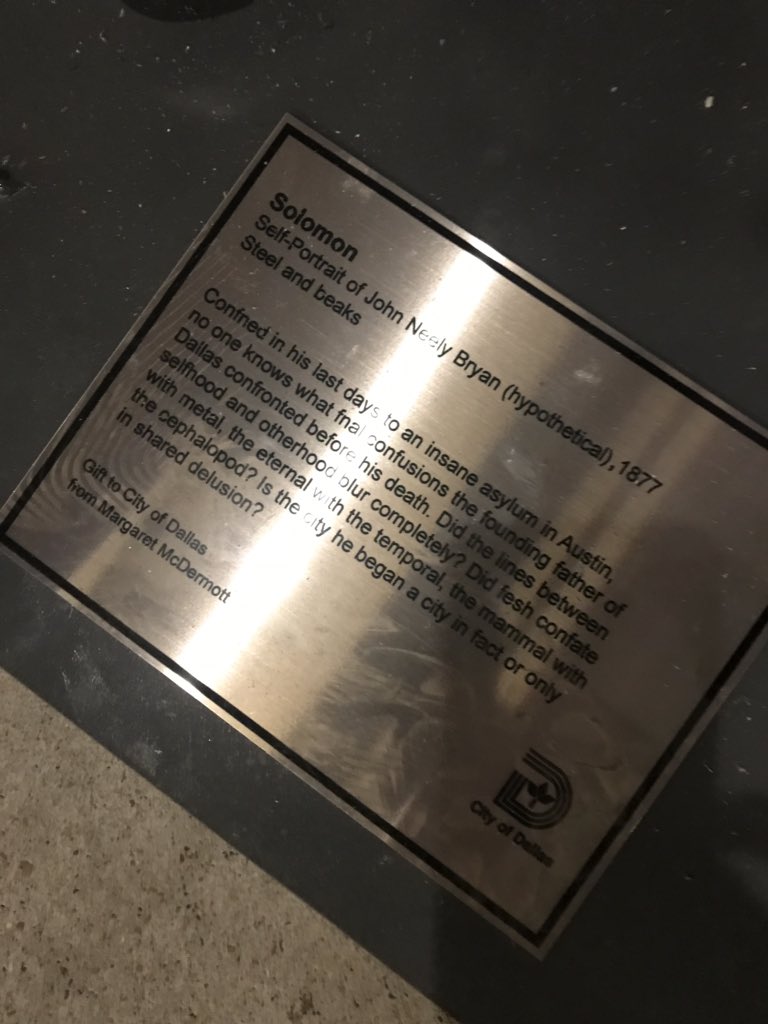

But while the oddity understandably piqued his immediate interest from afar, things got even weirder up close: At its base, the piece featured a plaque indicating that the sculpture was a representation of John Neely Bryan, the man credited with the City of Dallas’ founding in 1841.

The cryptic passage about Bryan that followed on the plaque was equally extraordinary: “Confined in his last days to an insane asylum in Austin, no one knows what fnal (sic) confusions the founding father of Dallas confronted before his death. Did the lines between selfhood and otherhood blur completely? Did fesh (sic) confate (sic) with metal, the eternal with the temporal, the mammal with the cephalopod? Is the city he began a city in fact or only in shared delusion?”

Beyond its own “hypothetical” claim that Bryan was half-man, half-cephalopod, just as dubious was the plaque’s claims that the piece — seemingly called “Solomon” — was a gift to the city from the late philanthropist Margaret McDermott, for whom one of Dallas’ Santiago Calatrava-designed bridges was named.

Photo by John Bradley.

It was all very wild — but also, frankly, a lot of fun to write about.

To no one’s surprise, we gleefully leaned into the weirdness at hand. First, we found an honest-to-goodness cephalopod expert who was happy enough to play along and answer our questions about the possibility that Bryan was somehow more than human. A few days later, when the statue was ushered away as quickly and as quietly as it had arrived because the city deemed it a “public safety hazard,” we breathlessly covered its removal and treated it as breaking news.

Weirdly, only one other outlet even bothered mentioning the saga at all in its regular coverage of the city — which was honestly fine and good by our measure, as it offered us some real ownership over the matter.

There were even some angles we pursued that didn’t pan out. Most of all, we wanted to find out who had been behind the prank. Following up on the Dallas Morning News‘ report that the statue had been removed by and was in the possession of Dallas’ Office of Arts and Culture, we placed a call into that city office to see if anyone had called them to claim ownership of the statue and request its return. Apparently not; officials at the OAC were so spooked by my question that I ended up patched through to a conference call featuring no less than three of the office’s workers. They said no one had called other than me — and they wanted to know why I was so interested in knowing.

What else, they asked, did I know? I promised them I knew nothing, that I was just charmed by the cheeky story. I’m not sure they bought it, and I’m pretty sure they still think I had something to do with its installation.

Thing is, I might’ve unwittingly known more than I thought I comprehended at the time.

At some point over the course of all this reporting on cephalopods and statues, I received a phone call that didn’t seem as weird in the moment as it would in hindsight. It wasn’t much on the surface; a phone number with a local area code simply called in to our business phone number to confirm our office’s mailing address. We get calls like these more frequently than you might expect, usually from publicists looking to verify information in their databases. This call was only somewhat strange in that the seemingly male voice on the other end of the line hung up as soon as we confirmed the information they sought.

But none of my red flags rose until a few days later when a mysterious package about the size of a shoebox showed up at our office — and with my own apartment building’s address listed as the return address, which is a chilling thing to notice on a package, to be sure.

The contents of the box were just as startling. Here’s what it contained:

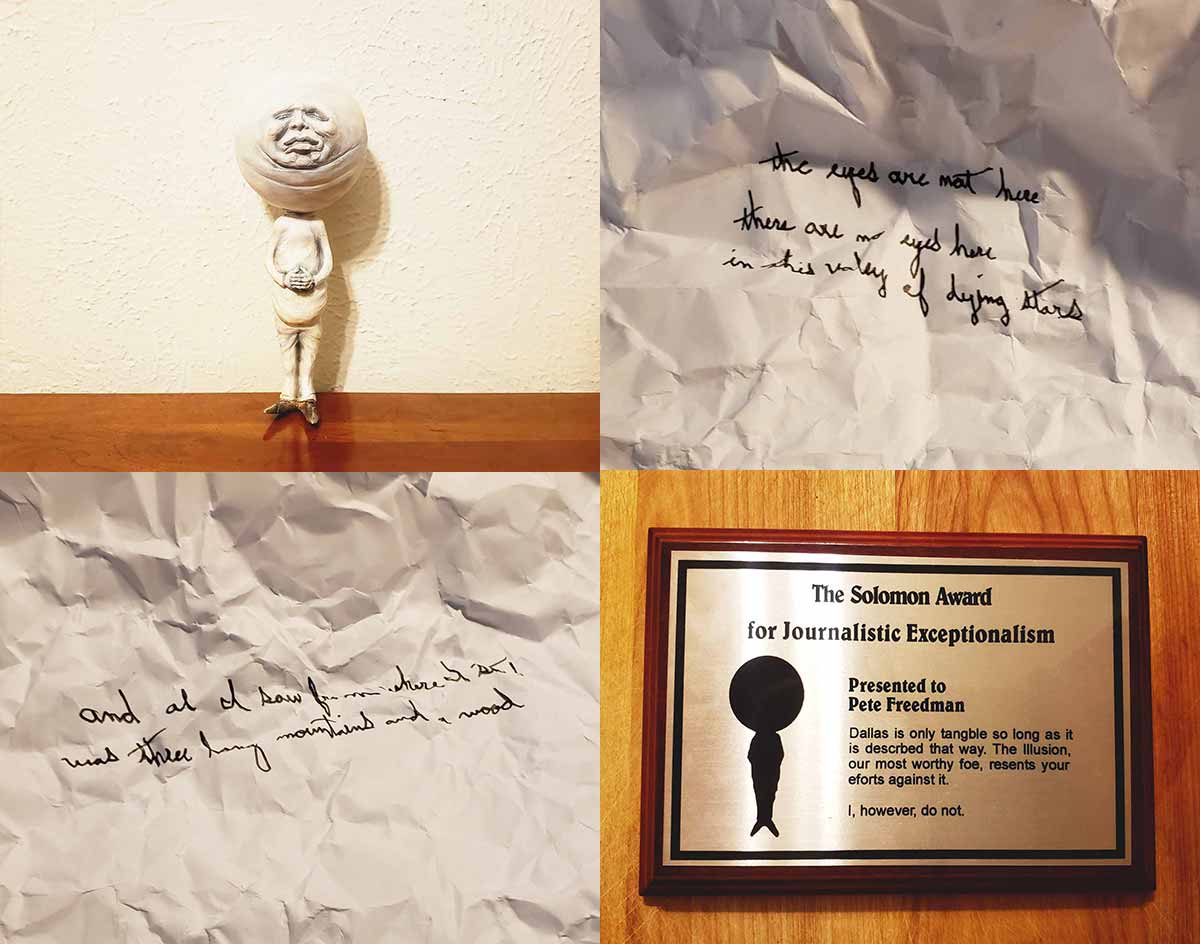

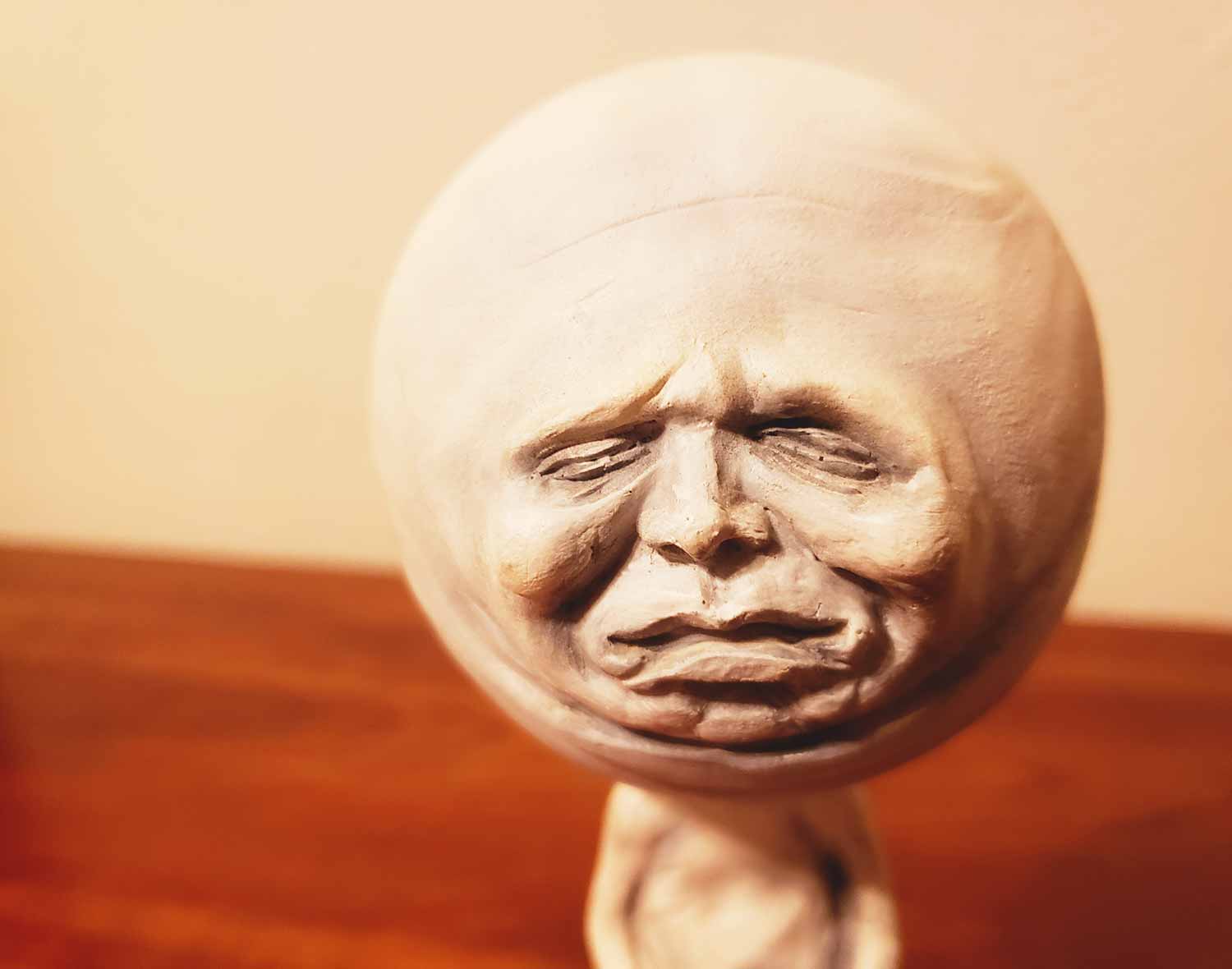

- a 10-inch ceramic humanoid statue boasting a large head with intricate features, carefully shaped hands and limbs, and metallic feet

- a plaque honoring me with “The Solomon Award for Journalistic Exceptionalism” and the inscription “Dallas is only tangible so long as it is descrbed (sic) that way. The illusion, our most worthy foe, resents your efforts against it. I, however, do not.”

- two crumbled-up pieces of paper featuring hand-written poem couplets — one cribbed from T.S. Eliot and the other swiped from Edna St. Vincent Millay

- a whole lot of shredded paper that served as packing cushioning and that seemed to feature more handwriting spread across its many remnants

I was taken aback, to say the least — but also, admittedly, more than a little peached by the plaque’s compliments. Even more than that, though, it made me only more desperate to know where these gifts came from.

I messaged Dan Singer, the writer of the Dallas Morning News piece, to ask if he’d received any mysterious packages at his office. Though he — rather weirdly, I should say — declined to comment on if he had, other sources I spoke with at the newspaper said they didn’t notice Singer getting any particularly notable pieces of mail of late.

I also called John Bradley, the man who first publicly noticed discovering the statue, to press him for more information. Somewhere along the way, a reader who works as a barista at a coffee shop that Bradley frequents reached out to me because they thought it was interesting Bradley was involved in this storyline. They described him as artistic-minded and said the whole thing sounded close enough to his sense of humor. When pressed on this, Bradley laughed. While he copped to finding the statue funny and compelling in the same way I did, he balked at the mere suggestion that he had an artistic bone in his body — and flatly denied any possible involvement between his busy work and home lives.

Around the same time, a Dallas musician I’ve written about extensively throughout the years reached out to me to suggest he knew who was behind all of the recent Solomon hijinks. He said he overheard a friend claiming credit for the ruse, but also said he didn’t feel comfortable sharing that information without getting the OK to do so. Alas, no answers would ever arise on this front. Wrote the musician after it was clear my continued pleading wouldn’t sway his position here: “Maybe it’s good for our sweet city to have its own myths.”

Still, there remained one final route to explore for more clues. Perhaps there was a clue to be found on the writing I’d seen on the shredded paper scraps in the package? At the very least, I figured, I could ask a couple interns to try puzzling the pieces together for a day or two to see what hints might be revealed. Certainly, interns elsewhere had been asked to do worse.

It was the end of a Friday workday when I resigned myself to exploring this path — or, fine, asking our interns to do it for me. I packed my things, including the plaque and statue, into my backpack and I ventured off into my weekend. I left the box, which was still filled with paper scraps, behind on my desk.

When I returned to the office the following Monday, I realized I’d made a horrible mistake: The package was nowhere to be found. I asked around with some officemates, who revealed to my dismay and horror that the cleaning crew had been in over the weekend. Presumably, they’d mistaken my treasure for trash — and left the investigation, perhaps fittingly but far more literally, suddenly clueless.

A funny thing happens when something so consumes your life as cephalopods had mine over the course of this journey. Maybe it’s like when you buy a car and you all of a sudden start to see other people driving your same car everywhere you look, but I became convinced that cephalopods were having a moment. Friends aware of my newfound obsession didn’t help matters by making sure I was kept abreast of all recent cephalopods discoveries, but it absolutely freaked me out that squids were such an integral part of the storyline on HBO’s The Watchmen. Could all of this really just be coincidence?

Over time — and a series of far more calamitous real-life events justifiably taking over the zeitgeist — my paranoia calmed some. Every now and then, though, I’d glance over at my bookcase, spot the miniature statue and plaque that I’d proudly placed on display as welcome trinkets, and wonder if I’d ever get to the bottom of this mystery.

A year later, I’m increasingly doubtful I will — for a few reasons.

For one, the attorney John Bradley? The guy who first shared news of the cephalopod John Neely Bryan statue to Twitter? Curiously, he deleted his Twitter account at some point over the last 12 months when I wasn’t paying attention.

And, secondly, when I rang up my musician source this week to plea for more information now, all this time later, he said that he no longer remembers who he once upon a time thought was behind the whole thing. Whether I believe him doesn’t really matter; fact is, I very much do believe he’s a man of enough integrity to not go back on the vow of secrecy he took all those months ago — for better or for worse.

Still, for a moment this week, I had reason to believe I might just crack this egg yet. As fate would have it, our website just so happened to recently profile the efforts of an East Dallas muralist who himself goes by the name of Solomon. Alas, it appears even that was mere coincidence: When I reached out to this Solomon to see if he was in fact the same as the other Solomon, he regretfully informed me that, much as he wished he could take credit for all of the artistic weirdness I’d become entranced by, it wasn’t his to claim.

Which leaves me… where, exactly? Honestly, I’m not really sure.

Here’s what I do know: For a few days in the fall of 2019, I became obsessed with the efforts of an artist whose identity I may never discover. I will, likely for the rest of my days, cling onto its memory as one of my most cherished wild-ass Dallas tales.

A thrilling conclusion this perhaps isn’t. But I still felt compelled just the same, a year later, to share the unique developments that occurred outside of the public’s purview when it came to this winding tale.

Why?

Well, I guess it’s like Solomon implied in his original offering to our city.

It’s when delusions are shared that they finally morph into something real.

All photos by Pete Freedman unless otherwise noted.