When A Fire Destroyed Much Of Dallas In July 1860, City Leaders Blamed An Imagined Slave Rebellion For Its Spark. Mass Beatings And Hangings Followed.

On July 8, 1860, a fire consumed Dallas.

It started on the southwest corner of town in a rubbish pile next to the W.W. Peak & Brothers drug store at approximately 1:30 p.m., just as most of the not-quite-yet-metropolis’ citizens were enjoying an afternoon siesta. Assisted by a southwesterly wind and a temperature reported to be as high as 110 degrees, the fire engulfed the entire community in mere hours.

Stores, hotels, the Dallas Herald newspaper (and its four presses) and virtually every structure in the city — along with most everything inside — completely burned to the ground.

Destructive though this particular fire was, it was just one of several to break out in this part of Texas at the time. Now, many blame the advent of phosphorus matches — “prairie matches,” these new models were called — and how volatile they could be in the extreme Texas summer climate as a common cause for those fire outbreaks. But Dallasites of the time had their own suspicions as to fire’s cause.

Before the Dallas fire of 1860, tensions in the city were already high thanks to rumor and news of abolitionists and slave uprisings, not to mention an upcoming presidential election and, of course, the looming Civil War. The year prior, in October of 1859, the militant abolitionist John Brown met his end at the gallows after being captured by Robert E. Lee during a raid on Harpers Ferry in what is now West Virginia. It was a dress rehearsal of sorts for the coming War Between the States, and suspicions of similar abolitionist activity in Dallas was likely being blamed for the fire before its last embers went out.

These suspicions too had assistance in fanning their flames. In the days following the blaze, Dallas Herald editor Charles Pryor sent letters to several other Texas papers, telling of a “most diabolical plot” uncovered by a “Committee of Vigilance” — a group of select city leaders whose goal was to ferret out such uprisings. Just like that, another fire (if only metaphorical) had sparked. The ensuing panic was called the “Texas Troubles.”

This “most diabolical plot” Pryor wrote of was little more than a role reversal of the status quo by which Dallas has always abided. It posited that the area’s enslaved Black people were planning to do to their White slavers many of the exact things that had been done to them: White people’s property was to be destroyed or taken, followed by their lives, and those of their wives and their children.

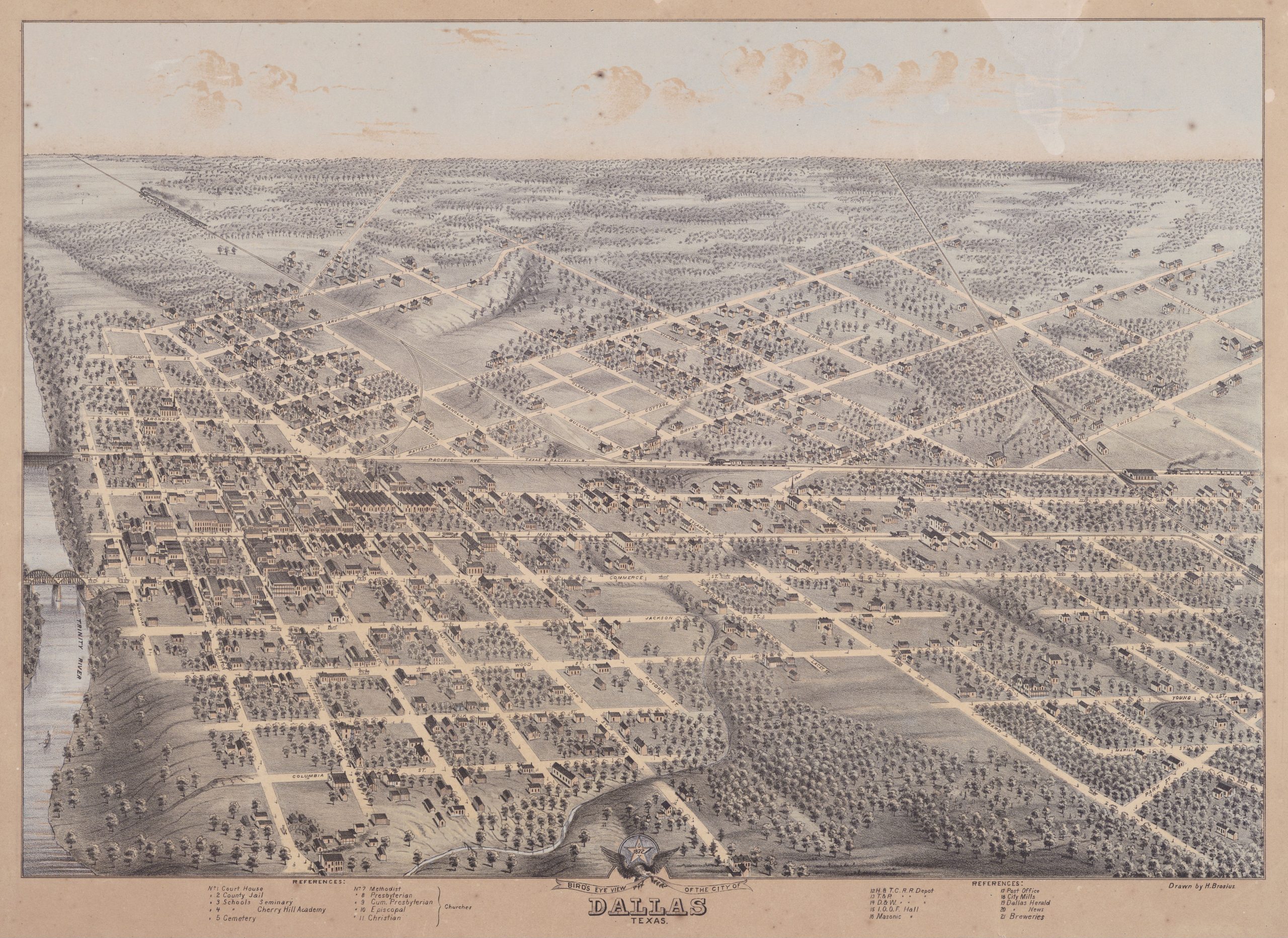

This map shows Dallas in 1872, a full 12 years after the fire of 1860. It’s the best approximation we can find of what Dallas looked like at around the same time of the blaze. (Right-click and open in a new window to enlarge.)

Naturally, such a threat — imagined as it may have been — would merit a real punishment, and this was Committee’s real purpose. These powerful men quickly portrayed the Dallas fire as being of a larger conspiracy — that it was the beginning of a black rebellion masterminded by two former Dallas residents who had been forced to leave the previous year: Solomon McKinney and Parson Blount.

McKinney, a Christian minister, was of the mind that Dallas’ human traffickers were inhumane in their treatment of the enslaved Black people — a view radical enough at the time to earn him the “abolitionist” epithet from his neighbors. Blount earned the same title just by defending McKinney of what was perceived as an insult.

(A tangential detail of pertinence: Around the time in which this all took place, McKinney had agreed to collect a debt from a man named Sprowle; this same man, Sprowle, helped incite a mob over McKinney’s alleged abolitionist rhetoric. McKinney, it should be said, was not actually an abolitionist; he just argued that many Dallasites crossed a line with especially horrid treatment of slaves.)

In the latter half of 1859, an angry mob captured, stripped and whipped Blount and McKinney each before forcing both men to leave the city.

Blount and McKinney never incited any insurrection, but they were also conveniently no longer in Dallas to defend themselves when theories broke out of conspiratorial activity that they’d allegedly provoked. Soon as the Committee of Vigilance settled on its satisfactory conclusion — one reached after 15 days of secret, torturous interrogation of nearly 100 slaves across the city — 1,071 of the 1,074 enslaved in Dallas were implicated in coordinating the arson and its suspected subsequent insurrection.

Talks of mass hangings followed.

But because enslaved people were legally property, and the human traffickers didn’t want to lose any more property after having lost so much in the fire, those talks stalled. One unnamed Dallas slave owner, faced with the potential lynching of the human beings he enslaved, apparently argued that “killing the Negro would really be robbing him.”

At the time, of course, cotton was king — yes, even in Dallas. As the city awaited the completion of a railroad that would connect it to Houston and beyond, and allow it to blossom into a center of business and trade, its residents readily justified utilizing enslaved cotton field labor forces to prop up their livelihoods. They didn’t view these workers in terms beyond profits and losses, though. One citizen summed up the decision to spare most of the enslaved from repercussion with chilling honesty: “Now, we must vote to hang them three negroes, but it won’t do to hang too many. We can’t afford it.”

This cruel irony saved the lives of all but “them three” — the alleged ringleaders among the enslaved. The remaining accused were whipped as a compromise, some more brutally than others, with many of the white men in the city reportedly “anxious and eager to lend their assistance.”

The next day, Samuel Smith, Patrick Jennings, and a third man known as Old Cato were to hang.

Smith was a preacher, a spiritual leader with associations to visiting abolitionist preachers. Jennings was described as an agitator, which is to say he was offensive to whatever sense of propriety white supremacists understood in 1860. Cato ran the mill of the family enslaving him, which gave him an uncomfortable amount of power and responsibility in the young city.

On July 24, the three were led through the blackened ruins of the fire, and were reported to have shown no outward emotion while approaching the banks of the Trinity where the gallows awaited. Patrick was said to have had a tobacco chew in his mouth as he nonchalantly surveyed the city; it even allegedly remained there as he expired, with his death taking the longest of the three.

Those whipped the day before were brought along to witness the lynchings — yet another horror to reflect upon. At least one member of the Committee of Vigilance, a Judge James Bentley, openly doubted the guilt of the three, but was quoted as justifying it by saying “somebody had to hang.”

Today, there’s a park named for these three murdered men right near where they met their end. But Martyrs Park is marked only by a simple sign — one found not too far off from where a U.S. president met his end — a death marked by a looming monument. Earlier this year, the City of Dallas’ Office of Arts and Culture posted an open call for artists to propose a “memorial for the victims of racial violence in Dallas” to be installed at Martyrs Park in the coming years, but the sign that stands there now is as of yet the only acknowledgement of what happened nearby. It simply says the park was established in 1963, but leaves out any inkling of who these “martyrs” might be. With the site of the JFK assassination just 100 yards to the east, and JFK’s own monument just past that, one might infer it is just another reference to JFK.

As July 24 and the 160th anniversary of these lynchings approach, this question remains: How can a city heal from its racist and violent past without publicly properly acknowledging it?

There are many who need healing in this city: The survivors, the witnesses, the perpetrators and those who further perpetuate it by pretending it doesn’t exist.

Dallas often pretends things don’t exist in the hopes that they will disappear. We see an echo of that in how some are handling this pandemic; quite literally, their masks are off.

But the mask is also off for those offering armed protection to statues and symbols representing the city’s history of racist violence. As monuments to the actual victims in this city are long overdue, Dallas continues to produce martyrs — some are self-professed, suffering a litany of imagined crosses and inconveniences.

Others are dead.

To heal as a city, we need to look in the mirror. And we need to better remember the real martyrs.